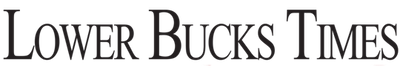

Franco Pagani has a bone to pick with his mayor: The long-standing public official won’t hang the portrait he painted of him.

It may be due to a misunderstanding, but Pagani doesn’t think so. Either way, he met Mayor Joe DiGirolamo years ago, after settling in Bensalem. Before that, a decades-long singing career he started in the North of Italy took him through Europe and into New York, and eventually to Philadelphia.

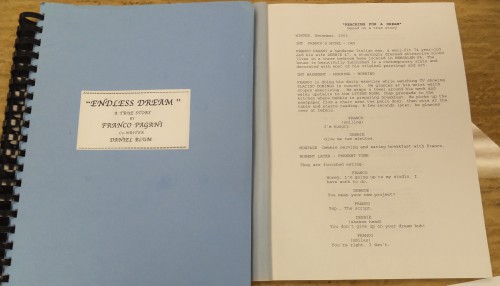

By the time Pagani reached Bucks County, he was years into working on his own opera, a two-and-a-half-hour traditional bel canto piece called Rosita. A labor of love and a leap of faith, he composed it an acoustic guitar and scored it by hand before connecting with a pianist who helped him arrange the full orchestration on a synthesizer and record it with singers from the Opera Company of Philadelphia.

DiGirolamo offered to help him get the opera published, and to thank him Pagani presented him with a portrait he painted based on a picture of the mayor. But things stalled there. Pagani can’t get any traction with Rosita, the story of a businessman who is falsely accused of murder while visiting Mexico, then escapes prison and meets a girl.

He’s gotten positive feedback from companies abroad, even if they said they don’t have the resources to mount new works. Closer to home, he said, the Opera Company of Philadelphia won’t even dignify him with a response. He got a nice write-up in the Courier Times a while ago, but today he can’t get any traction with the Philadelphia Inquirer even after providing them with the finished opera on CD.

And, he can’t get DiGirolamo — or former Pennsylvania Gov. Ed Rendell, or Mayor Michael Nutter of Philadelphia, or any other host of public officials whom he’s painted — to hang his works, or even acknowledge him publicly.

One of his latest paintings is entitled Jesus Welcomes the Pope, and he’s scheming to get it to Pope Francis when the pontiff visits Philadelphia in September. But he doesn’t have an in, or much of a plan past the idea that just heading down to Ben Franklin Parkway with the large canvass isn’t really feasible.

Instead, he rhetorically threatens to take his paintings to City Hall in Philadelphia some day and burn them. That way, at least, he’ll get some attention from the news.

In fact, that’s part of the reason, he believes, he’s not getting anywhere with his opera: Nobody cares about a work, even a decades-long labor of love, conceived, written, scored, recorded and paid for piece by piece, if the person who wrote it isn’t already well-known.

Pagani believes he should at least be recognized for his career in show business, if not his magnum opus. But he doesn’t trust agents or publicists after some bad dealings during his singing days, and believes he should be able to obtain the merit he wants based on his past accomplishments and what he produces today.

By his own admission, the paintings are an attempt to get a foot in a door, a way to gain some exposure and credibility so maybe people will give more consideration to his opera.

And for the record, DiGirolamo never did promise to hang the portrait, and at the least not while he’s still in office. According to Barbara Barnes, the administrative assistant for the mayor, DiGirolamo did graciously accept the unsolicited gift. The mayor also honored Pagani’s request to have it returned when Pagani accepted the fact that it wouldn’t be hung up, nor would the township hold the gala unveiling the artist envisioned.

Furthermore, Barnes said, DiGirolamo did contact various musical institutions on behalf of his constituent in an effort to get Rosita picked up. But the mayor is not in the music business, she noted, and there’s only so much they can do.

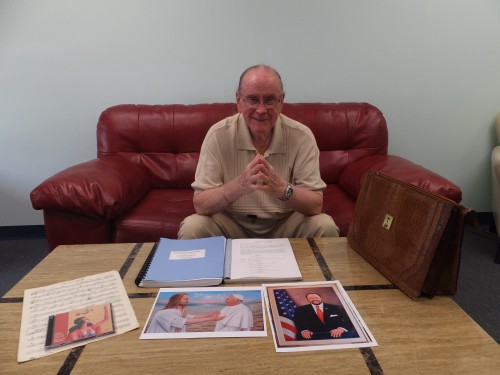

It’s not the conclusion he wanted, and it’s not the first story that didn’t go his way. Even Pagani’s autobiographical screenplay doesn’t end how he wants it to. It’s here he tells the story of first coming to America in 1965. Born in Italy, he began singing in church and eventually toured Europe while recording for Polydor records in Germany and RCA in Belgium.

His first gigs in the states were engagements at Carnegie Hall and Madison Square Garden in Manhattan as part of a package shows of Italian performers. From there, he performed on regional tours and steady gigs in New York City, and made more records of his own music.

The screenplay mostly focuses on his residency at the Latin Quarter Club in Manhattan during the 1960s, well before he moved to Philadelphia and became inspired to write his own opera.

Entitled Endless Dream, it’s technically 109 pages long. He was hoping to tell the part of the story where the opera gets produced, but couldn’t wait any longer and had to finish it. This is noted in the text, which ends on page 108 and leaves the last one blank.

Pagani may be an unknown now, but his work as a songwriter and performer supported him for decades. He’s happy personally, he says, with his career and his output, but there’s a creeping bitterness to his stories about how he’s regarded at large.

His records are long out of print, but vestiges of his work can still be found online, notably where a fan of Italian language music posted tracks from Pagani’s record El Corazon de Italia on YouTube. There are also a few snippets of Rosita from a single performance in Italy, where selections from it were performed in a church with a piano and singer in the ‘90s.

The opera isn’t a dud, at least gauging by the applause on those videos and according to the few responses he’s gotten. A conductor abroad, whom Pagani contacted, took the time to listen, play through the score himself, and provide him with nuanced, detailed responses about the music. He also expressed regrets that his budget wouldn’t allow the company to mount a new work.

For this article, I lent a copy of Rosita to a music store owner and longtime subscriber to the Opera Company of Philadelphia. If it were written a hundred years earlier, he suggested, when opera was more popular, it would have made it to the stage.

Pagani began working on Rosita more than 20 years ago after noticing that traditional bel canto operas consistently played to larger crowds than modern works. He’d always written his own songs, and was inspired to create his own traditional bel canto — “beautiful singing” — opus. At the same time his voice began faltering, so he opted to write rather than give substandard performances.

Instead, he worked for years as a manager in an Italian restaurant and spent his off-time composing Rosita. Later, he’d start driving out regularly to Bala Cynwyd to have it orchestrated on a synthesizer and finally recorded with professional singers.

The professionally printed double CD of Rosita is essentially a demo recording, but a good one. The writing and arrangements are strong, and only on some of the softer passages do the limitations of the synthesized orchestra start to show.

It’s a shame, then, that only a handful of people have heard it. Perhaps it was all timing conspiring against him. He came to America just as the Beatles were changing the face of popular music. Later, he wrote a new opera when most companies could barely afford to produce well-known pieces, let alone mount a new production from an untested composer. Even the Courier Times feature, which maybe could have given his efforts a boost, came out at a bad time: it ran on Sept. 10, 2001.

Now he’s mostly slowed down, only occasionally approaching opera companies or newspapers, or painting portraits. And while he may not push as hard anymore, he still knows what he wants.

“In your write-up, I’d like it to say, ‘We have a renaissance man lost in the shadow of Bensalem,’” Pagani said, shortly after reaching out to the Midweek Wire.

That, at least, would be a start.